What is Intersectionality?

The term “intersectionality” was first written about by American scholar and civil rights activist Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989 to describe how people experience oppression in multiple, intersecting layers. Earlier forms of this concept may trace back to the late 1800s in Black feminist thought circles that included scholar and educator Anna Julia Cooper and abolitionist and activist Sojourner Truth.

A gay man faces homophobia, and a Black man faces racism, but a Black, gay man faces homophobia and racism, often at the same time. He may face racism within the queer community and homophobia within the Black community. Thus, his experience differs from a white, gay man, as well as from a straight, Black man. Similarly, an undocumented, disabled, transgender Latinx womxn faces transphobia, racism, ableism, sexism and discrimination based on immigration status. Within each of these communities, it is likely she faces discrimination against her other identities.

Oppressive identities are not just additive, but multiplicative in their consequences. Experiencing the world as an autistic person and as a queer, non-binary person are different, but these identities are experienced simultaneously. Intersectionality looks at the privileges experienced within marginalized groups and asks why other members are denied those. Through understanding intersectionality, we realize that one experience of oppression doesn’t fit all. When one social movement fails to examine intersecting oppression, that social movement will often replicate and reinforce the oppression of other groups.

Intersectionality is an important concept for understanding that everyone’s experiences with oppression are individual and unique. Activism that focuses purely on one oppressed group with no acknowledgment of intersectional experiences will fail to fully liberate the members of that group. For example, an LGBTQIA+ movement that ignores the needs of its members of color will not succeed because even if the movement achieves all of its goals, members of color within their community will continue to suffer from racism. As we fight for justice and equality for all people, not just the one factor that makes us different, but for every factor that makes up our full, authentic selves, it is essential to recognize that a lack of intersectionality undermines all of our movements.

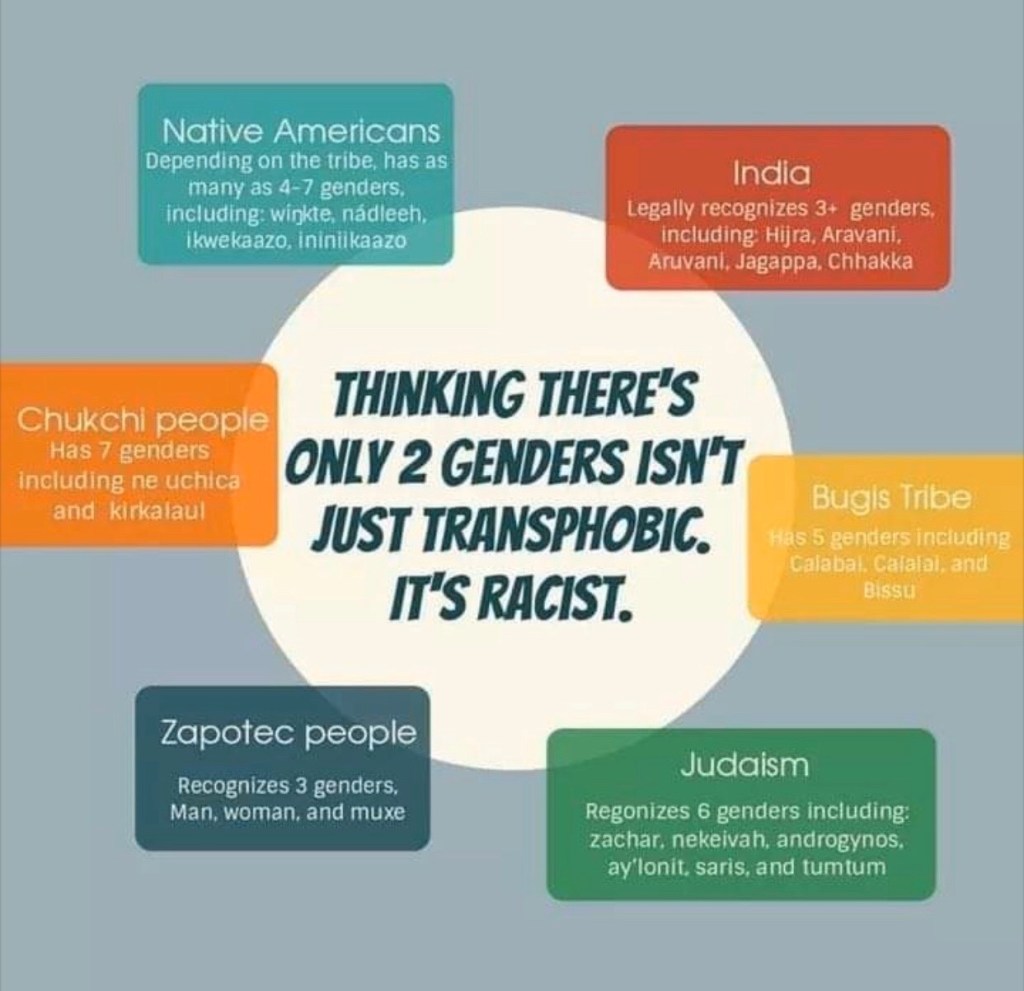

When thinking about intersectionality, there are many identities to consider: socioeconomic status, race, gender, age, sexuality, ability, neurotypicality, immigration status, nationality, body size, criminal history, diet, ethnicity, health, aboriginality, occupation, education, religion, spirituality, language, geographic location, political affiliation, veteran status, heritage, trauma history and family status. Intersectionality acknowledges that there are intragroup differences within groups of people with a common identity.

History

While the LGBTQIA+ movement has become largely white and male, it began with transgender womxn of color rioting at the Stonewall Inn in New York City. Marsha P. Johnson, a transgender Black womxn, and Sylvia Rivera, a Latinx trans womxn, are rarely acknowledged at Pride and other LGBTQIA+ events.

In the 1960s, the Gay Liberation Front marched with the Black Panthers to protest the Vietnam War. At this time, gay men and Black men were largely targeted by law enforcement and worked together on issues like police reform. Additionally, this movement was full of anti-capitalists like Harry Hay, who founded the early LGBTQIA+ organization the Mattachine Society. The first Pride march occurred in Washington D.C. in 1989 and included a conference that encouraged partnerships between different racial groups, including the National Organization for Women and the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays.

Why is Intersectionality Important?

Viewing any one group as a single homogeneous community obscures the voices of that group who experience oppression due to intersecting identities. The LGBTQIA+ community especially has a history of excluding and erasing intersectional members. Many LGBTQIA+ groups have little knowledge of race or ability issues. When organizations do not address the intersecting issues that affect their members, they often perpetuate oppression and create unsafe spaces for individuals with marginalized identities. For example, an organization that does not address how classism affects many members may throw events with steep entrance fees that low-income members can’t afford. Additionally, Pride has erased its history of transgender womxn of color and is now a corporate event, where the same corporations that oppress and imprison trans and non-binary folx of color are the sponsors. Furthermore, the LGBTQIA+ movement has largely failed to support #BLACKLIVESMATTER, despite the fact that the majority of #BLACKLIVESMATTER leaders are LGBTQIA+. This is directly connected to how the mainstream LGBTQIA+ movement refuses to acknowledge, analyze and address race.

Marriage equality was the major LGBTQIA+ ticket issue in the last couple decades; however, marriage equality fails to acknowledge the history of criminalization of LGBTQIA+ bodies, something the LGBTQIA+ community has in common with communities of color. Marriage equality did not change the incarceration rates of queer Black, indigenous, people of color, nor did it end the racial profiling of LGBTQIA+ BIPOC, nor the high suicide rates of these communities, nor the lack of health care. In order to fully liberate its members, the LGBTQIA+ movement must address racism in the criminal justice system, and the intersectional issues that affect community members.

Due to its lack of intersectionality, the LGBTQIA+ movement has pushed out sub-movements that are wholly inappropriate to many members with intersecting identities. During the fight for marriage equality, many LGBTQIA+ individuals, especially, white, gay men, pushed closeted individuals to come out. Some went so far as to claim it is their responsibility to the community and movement to come out, in order to change people’s views. However, coming out can put many individuals in physical, emotional and spiritual harm. To some, coming out could mean exile or a loss of shelter, clothing and food access. The belief that every LGBTQIA+ individual must come out assumes that they all will find communities to uplift and celebrate them; devastatingly, this is not true, especially for community members with intersecting identities. A low-income, transgender, single mother may choose not to come out because they could risk losing their job, house and child. An undocumented, gay, Latinx man may choose to not come out because being undocumented is dangerous enough. For them, choosing to not come out is just as much an act of resistance and survival as coming out is for others. The more intersecting layers of oppression a queer person faces, the more dangerous and difficult coming out can be. Choosing to not come out is not an act of dishonesty but an act of honesty about what is best for an individual at that moment.

Additionally, the It Gets Better movement is another LGBTQIA+ sub-movement that fails to address intersectional differences. The IGB movement was largely created and pushed by wealthy, white, cisgender gay men and encourages young members of the community to continue living for the promise that their lives will get better with time and age. However, this movement fails to understand that for members who are not wealthy, white, cisgender, male, documented, able-bodied, neurotypical, thin, etc., it is much less likely that their lives will ~magically~ improve with age and time, especially if the LGBTQIA+ movement continues to fail to address the intersecting oppressions they face.

Intersectionality enables us to be our full, authentic selves, rather than fragmenting our identities into separate communities. Instead of focusing on one, singular movement at a time, intersectionality demands that all of our identities come first and at the same time.

Intersectionality asks why we are unable to connect our oppression and struggle for justice with the oppression and struggles of other groups. Why can we acknowledge our own oppression and demand justice but turn a blind eye to the oppression of others? Doesn’t all oppression and discrimination come from the same place – the fear of difference? If we only advocate for acceptance of one differing identity at a time, we are just displacing that fear onto other groups. Intersectionality is essential to achieving justice for all because it demands acceptance of all differences, simultaneously.

How to be an Intersectional Activist

- Acknowledge and use your privileged identities to elevate the voices of trans and non-binary people, especially those who are Black, Indigenous and of color.

- Advocate for trans and non-binary people in leadership positions.

- Continuously reflect on the ways in which race, class, gender, age, ability, neurotypicality, immigration status, body size, criminal history, diet, ethnicity, health, aboriginality, occupation, education, religion, spirituality, language, geographic location, political affiliation, veteran status, heritage, trauma history and family status affect our communities. Acknowledge and name biases in yourself and others. Be honest about where your fear and anger come from.

- Join marches and protests that are not necessarily just for the LGBTQIA+ community.

- Embrace the discomfort of difficult conversations. Be an ally to all oppressed groups, all the time, even when it’s uncomfortable.

- Create safe spaces for intersectional identities within the community and organizations.